Giant Baba: What Only Hardcore Fans Know About The Founder Of All Japan Pro Wrestling

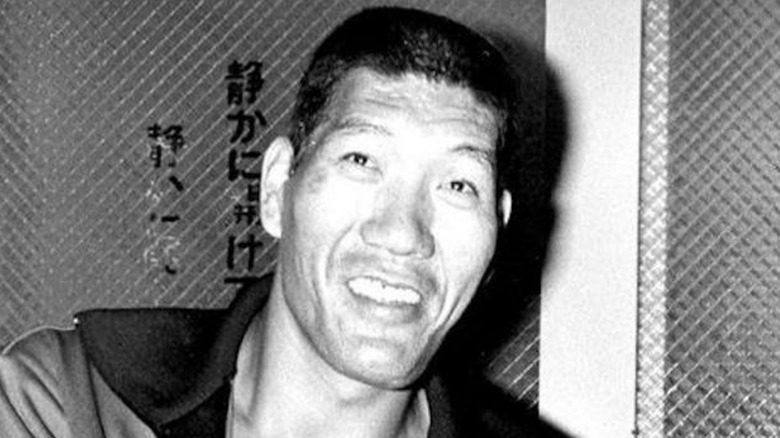

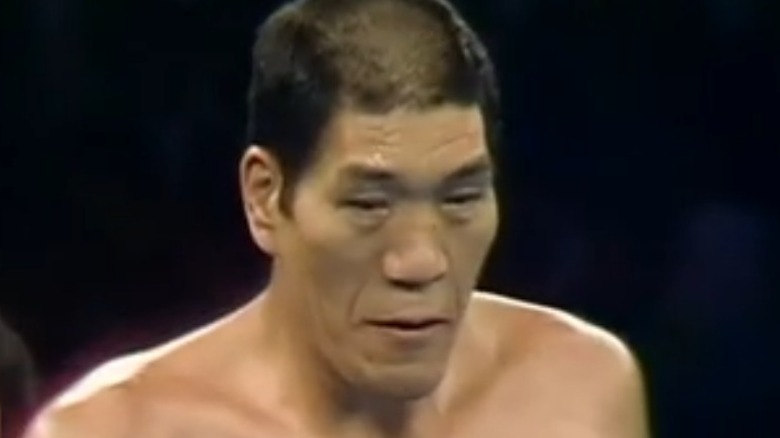

Giant Baba, real name Shohei Baba, was one of the most influential figures in the history of professional wrestling, particularly in his native Japan. As a top star for decades as well as the promoter of All Japan Pro Wrestling, Baba was a mover and a shaker, widely respected for giving his talent first-class treatment in a business where that was a rarity. He stood in contrast to more colorful rival Antonio Inoki, the founder and top star of rival New Japan Pro-Wrestling, who he broke into the business with in 1960.

But there's a lot more to Baba than just being Inoki's promotion rival, as both the booker and promoter who orchestrated arguably the most talent-dense main event scene in wrestling history, and the wrestler who had memorable matches with the likes of The Destroyer, Jack Brisco, Jumbo Tsuruta, Fritz Von Erich, and others. So with the caveat that some of these might be a little more less obscure to Japanese-speaking hardcore fans, let's take a look at some of Baba's history that isn't as well-known to western fans.

He fought for all three major world titles in a three week span in 1964

In the first few years of Giant Baba's career, most of his time from roughly July 1961 through March 1965 was spent on "learning excursions" in the United States. During this time, he became a pretty big attraction, main eventing across the country, but the peak of his stardom in America can arguably pinpointed as being in February 1964. That's because, within just a few weeks' time in that single calendar month, Baba got shots at what were considered pro wrestling's three "legitimate" world heavyweight titles at the time, belonging to the National Wrestling Alliance, the World Wide Wrestling Federation, and the World Wrestling Association.

It started on February 8 at Cobo Hall in Detroit, with Baba losing to NWA Champion Lou Thesz in a best 2/3 falls match that drew a strong crowd of what the Detroit Free Press reported as 9,188 at Olympia Stadium. A rematch at Cincinnati Gardens a week later drew 6,124 fans according to The Cincinnati Enquirer, but just two days after that, Baba would find himself getting another world title shot, this time at Madison Square Garden in New York City for Bruno Sammartino's WWWF Title. That match, which Sammartino won with a pair of backbreakers, drew 14,764 fans paying $44,218.96 according to the New York Daily News the next day. (Adjusted for inflation as of September 2022, that gate would have the buying power of around $425 thousand today.) Finally, Baba's shot at Fred Blassie's WWA Title in front of 10,400 fans at the Olympic Auditorium in Los Angeles according to CageMatch.net would at least net him a moral victory: A time limit draw after they split the first two falls of a 2/3 falls match.

It's a unique achievement that's unlikely to have been repeated in that era with how few traveling star attractions there were.

He had some impressive political power in Japan

With celebrity and money come power and influence. For Giant Baba, there's no greater example of that than the trouble he was able to get Steve "Dr. Death" Williams out of over the years. Specifically, Williams was busted trying to bring increasingly large quantities of drugs into Japan a whopping three different times over the years, in 1988, 1995, and 1997. (He started working for Baba in 1990.)

The 1988 bust at Detroit Metro Airport was, per a contemporaneous story in The Oklahoman, relatively small: Less than an ounce of cannabis and a few grams of cocaine and psilocybin mushrooms. What happened on March 20, 1995 was a different story: Contemporaneously, it doesn't appear that the specifics were ever reported. The main details that went public he never left Narita International Airport in Japan before returning home to the U.S. (per Dave Meltzer in the April 10 Wrestling Observer Newsletter) and that he "was suspended for out of ring conduct that was potentially embarrassing to All Japan" (per Wade Keller in the April 8 Pro Wrestling Torch). Meltzer would later report in his Williams obituary in the January 11, 2010 Observer that Williams was caught with cannabis at Narita, resulting in a one year suspension from AJPW.

He did, in fact, come back a year later, thanks, according to Meltzer in the 2010 obituary, to Baba. That was the last time "Doc" was busted in Japan, but, per the March 24, 1997, Observer, he was busted in the U.S. again on March 17 in Laredo, Texas, this time trying to bring in 121 boxes of painkillers and 41 boxes of tranquilizers. A week later, Meltzer cited Baba's pull as what allowed Williams into Japan days later to start wrestling on March 22.

To put Baba's sway in perspective, Paul McCartney — a much bigger celebrity — couldn't come back to Japan for a decade after his own pot bust at Narita.

He had a posthumous retirement match of sorts

On May 2, 1999, AJPW held a memorial show for Giant Baba at the Tokyo Dome. In addition a loaded card that included the return of the Road Warriors and a pair of first-time-ever matches in Toshiaki Kawada vs. Hiroshi Hase and Big Van Vader vs. Mitsuharu Misawa, it featured a memorial ceremony for Baba. That ceremony, though, was formatted to serve as, in a manner of speaking, the retirement match he missed out on.

The Destroyer, Gene Kiniski, and Bruno Sammartino entered the ring to the theme song from the AJPW TV show and went to their respective corners as if we were getting a Destroyer and Baba vs. Kiniski and Sammartino match. There was even an on-screen graphic treating it as a match, with AJPW's most legendary referee, Joe Higuchi, there to serve as the honorary official. The ring announcer introduced them one by one, his voice breaking when he finally got up to Baba, whose image was plastered on the giant screen in the Tokyo Dome outfield. After a speech from Lord James Blears, the figurehead president of the fictional PWF sanctioning body that oversees AJPW, Baba's widow, Motoko, placed his boots in the ring for the proper memorial and ten bell salute. And so ended, symbolically at least, the career of Giant Baba.

"I don't think something like this could ever happen in the U.S., and certainly not on this magnitude," wrote Dave Meltzer in the May 24 Wrestling Observer Newsletter after watching the ceremony. "Even though Motoko is probably the most feared person in Japanese wrestling, it was unusually touching to see her after this was over, crying heavily, sitting next to Baba's boots, and then grabbing the boots and putting them right next to her."

He was briefly a pitcher for the Yomiuri Giants

Shohei Baba's athletic career did not start with professional wrestling. Originally, as a teenager, he was a baseball player, leading to a somewhat fruitful minor league career, and a brief major league stint as a pitcher for the Yomiuri Giants when he was just 19. As recorded by Baseball Reference, he only pitched three games for the Giants, with an earned run average of 1.29.

A 2021 article in Numbers, a Japanese sports magazine, helps fill in the gaps beyond the easy to find statistics. It's not that Baba was a particularly explosive athlete or a crafty pitcher, the article explains, so much as his height made his pitches tricky to hit. Tsuyoshi Watanabe, former head of the Sanjo Business Baseball Club, was quoted by Numbers as expressing frustration that Baba couldn't put more speed on his pitches. That said, he was the youngest player in the league at a time when dropping out of high school to play professional baseball was exceedingly rare.

He's the Cal Ripken Jr. of professional wrestling

Cal Ripken Jr., the baseball legend who spent his entire career with the Baltimore Orioles, is probably best-known for his consecutive games played streak: 2,632 over the course of over 16 years from May 30, 1982 to September 19, 1998. Throughout that entire period, he never missed a game he was scheduled to play in. In pro wrestling, there's only one name that comes to mind as far as having a similar record: Giant Baba, who made his bookings for 3,764 consecutive matches from his debut in 1960 through suffering a neck injury in April 1984.

"[The total] realistically is more than 4,100 because his American matches weren't included in that figure," wrote Dave Meltzer is a Baba obituary in the February 8, 1999 issue of his Wrestling Observer Newsletter. A few months earlier, in December, Baba had missed two matches in a row — bouts on the undercard of the 13th and 14th cards of the Real World Tag League tour — without an announced injury, with Meltzer reporting in the obituary that "rumors quickly spread that his health problems must be serious." Baba did come back for the two final nights of the tour, but, per the January 18 Observer, he subsequently skipped a planned vacation which was to include the December 13 WWF Rock Bottom pay-per-view event in Vancouver. That was it for his career, as he had bowel surgery on January 8, turned 61 on January 23, and died due to complications from bowel cancer on January 31.

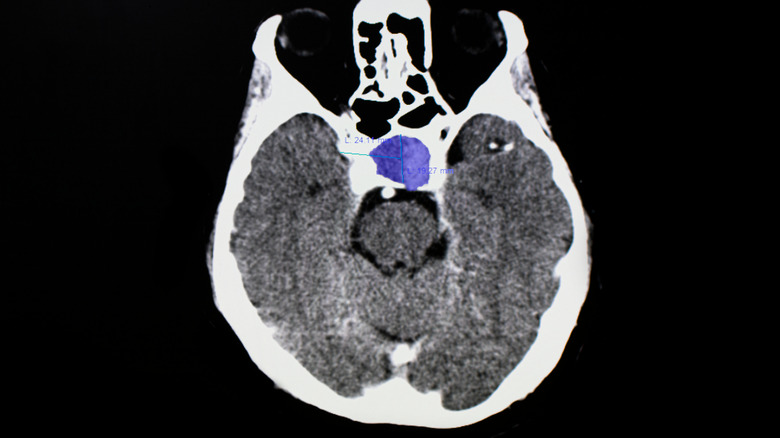

He had surgery to remove a brain tumor when he was 16

A different 2021 Numbers article recounts something else from Giant Baba's teen years, this one pertaining to his health. "In the off-season, I noticed that my eyesight was deteriorating," they quoted Baba as saying (roughly translated using DeepL). "I couldn't see five meters anymore ... I went to the hospital in a panic and was told, 'The pituitary gland is pressing on the optic nerve, and if you don't have surgery, you will lose your eyesight. Even if you have surgery, there is only a 1% chance of complete recovery.'"

On December 22, 1956, neurosurgeons at the University of Tokyo performed a craniotomy, opening up Baba's skull to remove the tumor in a surgery that lasted 80 minutes. The procedure saved his vision, but it did not stop the progression of the gigantism that the underlying pituitary gland tumor caused.

Baba and Antonio Inoki debuted on the same day on the same card

Though Giant Baba and Antonio Inoki would become the most powerful men in Japanese wrestling as the promoters and top stars of AJPW and NJPW, respectively, their personal history went a lot deeper than that. Specifically, they were both recruited by Rikidozan, the all-time legend of Japanese wrestling, at the same time, trained alongside each other, and debuted on the same card, JWA International Competitions Of The Summer 1960 night four at Taitoh Ward Gym in Tokyo on September 30, 1960.

A 2022 Number article helps flesh out the details around that period a bit better. With Baba winning his debut while Inoki lost, it was clear that Baba was being put on more of a fast track to superstardom. Baba would embark on a years-long excursion to the United States, where he got to learn how to be a main event level star. Inoki, though, spent the time that Baba was in America as Rikidozan's live-in valet, all while he underwent "training" that featured "daily beatings."

A war between two TV networks help facilitate Baba's launch of All Japan Pro Wrestling

According to a 2022 article in Number, the beginning of the end of the JWA came in 1969. While the JWA was a big ratings success for Nippon TV, they didn't have an exclusive deal. Knowing this, NET (now TV Asahi) approached the JWA about broadcasting cards that weren't shown on NTV. For the JWA, it was an easy call, as Japanese networks have always paid rights fees, but they felt enough loyalty to NTV to seek informal approval of the NET deal. NTV brass were fine with it under one condition: Baba couldn't appear on NET, which made room for Inoki to become NET's top star.

In time, Inoki would be forced out of the JWA, with his allies double-crossing him when he tried to take over the company while claiming he was trying to expose embezzlement. With Inoki gone by 1972, replacing him with Seiji Sakaguchi and Kintaro Oki as the top stars on NET didn't click, as TV ratings dropped from about 15% to under 10%. You can see where this is going: NET asked for Baba matches, the JWA went to NTV asking for permission, and NTV refused, saying they'd drop their JWA show if Baba appeared on NET. NET responded by saying they would be the ones to cancel JWA programming if they didn't get Baba matches, setting a deadline of the end of March 1972 to schedule April broadcasts. The JWA blinked first, NTV sought an injunction to bar Baba from wrestling on NET, and NTV canceled their JWA programming.

At that point, Baba and NTV began secretly planning the launch of AJPW, which NTV provided the start-up capital for. On July 29, he publicly resigned from the JWA en route to launching AJPW in October.

He developed a reputation as a particularly isolationist promoter

In the 1990s, Japanese wrestling changed a lot. Before, independent promotions were few and far between. You had "university wrestling", which was basically a cadre of college clubs doing glorified backyard wrestling, but that was about it. The proper independent scene blew up in the '90s with the likes of FMW, founded by AJPW alumnus Atsushi Onita, leading the way. NJPW was more than happy to work with these new groups, but Giant Baba's AJPW? Not so much.

This is probably best explained via Dave Meltzer's summary of an interview with Baba in the August 15, 1996 edition of Nikkan Sports, which he published in his Wrestling Observer Newsletter cover dated August 26. "Baba said that his wrestlers would never wrestle against New Japan because of the long standing rivalry," he wrote. "[T]hey would never do interpromotional matches against Big Japan, IWA or WAR because those groups are either run or headlined by, respectively, Shinya Kojika, Tarzan Goto and Genichiro Tenryu, all of whom were former All Japan employees, I guess because there are bitter feelings with Baba over the way they all handled their exits."

He didn't rule out working with the UWFi, then on death's door, though, and in the last few years of his life, he did start booking some independent wrestlers, but only from promotions not run by former AJPW talent. Aside from those few exceptions, though, AJPW stuck out as uniquely isolationist in the 1990s Japanese scene.

The Baba/Inoki tag team reunited only one time after they split to form AJPW and NJPW

Throughout the 1970s, AJPW and NJPW were at war, with no signs of a truce, but there was a brief respite in 1979. As Dave Meltzer explained in the April 25, 2011 edition of his Wrestling Observer Newsletter, the publishers of Tokyo Sports wielded so much power that, for the publication's 20th anniversary, they were able to get AJPW, NJPW, and the smaller IWE to work together on a one-off supercard. As a 2018 feature in Number explains, the offer was hard to refuse because the promotions involved didn't have to front the expenses, but all three would share in the profits.

There were still hurdles to clear, though. As the Number article explains, Giant Baba asked that Antonio Inoki apologize for past comments he had made, and Inoki refused, but they eventually hashed it out privately. The obvious main event that fans wanted was Baba vs. Inoki, but negotiating an outcome there would be impossible, so the call was made to reunite their JWA-era B.I. Cannon tag team. Their opponents would, naturally, be top heels Abdullah the Butcher (AJPW) and Tiger Jeet Singh (NJPW).

The match went off without issue until just after the finish. After Inoki pinned Singh and the two sides brawled, the heroes celebrated ... and then Inoki grabbed the house microphone. "I will continue to work hard so that I can fight Baba!" he said according to Number (roughly translated using DeepL). "The next time we meet in the ring, it's time to fight!" Baba accepted and they hugged, but he was silently fuming: Inoki never asked if he could issue that challenge. Baba decided that Inoki couldn't be trusted, and they never teamed again.